Expert Hubs 2021: the circular economy

28 October 2021

Europe faces a tough road ahead to realize its lofty ambitions in the semiconductor space

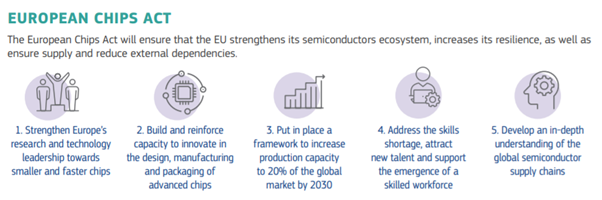

In February, the European Commission (EC) proposed the European Chips Act, a sweeping plan to reinvigorate the continent’s stagnant semiconductor industry. The need for greater independence has become increasingly clear in the wake of global shortages that have heavily impacted its member states over the last few years. This has affected not only consumer and commercial procurement of computing devices and smartphones, but also key manufacturing segments like the automotive industry, which is increasingly reliant on chipsets.

The Act sets an ambitious goal of doubling the EU’s share of global semiconductor production to 20% by 2030, fuelled by the mobilization of around US$49 billion of public and private sector investment. While the rhetoric surrounding the Act and the strategic focus on the semiconductor industry are to be applauded, it should be noted that in 2013, the EU announced the same market share goal to be achieved by 2020 and made almost no headway in that timeframe. History seems set to repeat itself this time around, as the specifics of the plan, the EU’s current industry position, and the future competitive landscape will all be significant hurdles to seeing success of this second effort.

Source: European Chips Act Factsheet, February 2022

Of the five action items outlined above, strengthening Europe’s R&D position, building a skilled workforce, and increasing knowledge around semiconductor supply chains to minimize the effect of future shortages are all realistic areas where improvements can be made. But in the realm of actually developing a meaningful domestic manufacturing base, the odds are stacked heavily against the EU. For one, luring one or more of the large semiconductor makers to foray into Europe will take significant subsidies, given the fact that there is little precedent for them to set up on the continent. The presence of a more complex regulatory environment in Europe, ranging from labor laws to sustainability requirements could also be a deterrent. The EC has shown a willingness to reconfigure its rules governing state aid to help attract companies for this project and will need to exhibit more flexibility down the line. And although the policies enabled by the Chips Act come from the bloc as a whole, the actual investment will still need to be driven by individual member’s national priorities, which could lead to competition between countries to the detriment of the larger goals at stake.

Furthermore, other large economies are eyeing up significant investments to increase their own capacities. The United States has a proposed $52 billion investment in chip manufacturing working its way through the legislative process, while also considering the creation of a semiconductor investment tax credit. South Korea has laid out plans for a whopping $450 billion worth of investment as well tax credits and deductions to enable companies like Samsung and SK Hynix to increase their production capacity by 2030. China, facing the additional heat of trade restrictions, has also affirmed its desire to move towards self-sufficiency in chip production. Competing against countries with a head start in the industry and that also have more streamlined processes for generating and allocating funding will be an uphill battle.

The EU should make sure it also focuses its efforts on the areas in which it already has competitive strength and which are crucial to the overall global picture of chip supply: chipset design and equipment manufacturing. Bolstering funding to empower startups and research institutions for chipset design is an easier path than constructing high-end 'mega fabs', and is also a crucial value-add step in the full chain of semiconductor production. Europe also has a strong position in manufacturing the equipment central to semiconductor production, with companies like ASML based out of the Netherlands. Securing a more dominant position in these areas will ensure Europe plays a role in the future of the semi-conductor industry without putting itself at risk of having nothing to show for its efforts.